Death in a crevasse

(by Christophe Peray, Translation by Karl Johannsen and Charlie Okiss )

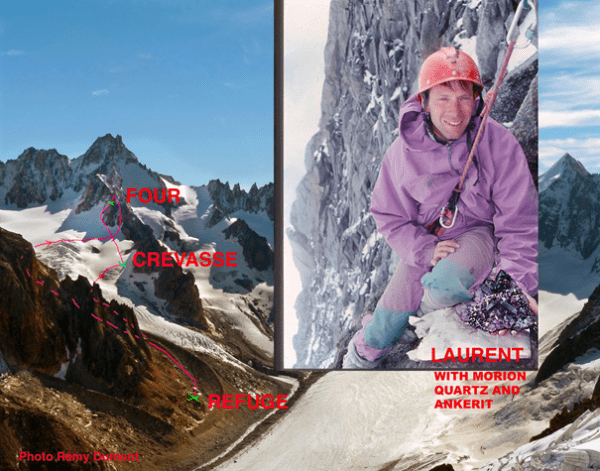

It was a godsend that a huge find of gems lay just two hours away from our way-station we called “the refuge” in the Argentiere. And so, my associate, Laurent, and I became partners and formed a team on the first of July, l993.

At first, all seemed to be going well.

But my new partner Laurent’s former colleague showed up at this alpine way-station. This “ex” could not accept that the two of them were finished being partners. Everyone knew that they had shared in three years of intense adventures there in the Argentiere basin.

Olivier Bielmann was manager of the refuge, our regular place to shelter when we worked higher up on the mountain. With the help from some of his staff, Olivier tried in vain all sorts of ways to find this fellow a new partner, even going so far as to suggest all three of us team up together.

But, Laurent had been clear : he would no longer team up with the “ex.” He wanted to keep relations friendly between them, but nothing more. He had his reasons, but he wanted it kept private.

I felt lucky to team up with him. Laurent Chatel was a very likable high-mountain guide with a solid knowledge of geology, from the University of Grenoble, and he was an excellent climber. He was an experienced gem hunter, a highly regarded expert in alpine mineralogy. He came from a place high up in the mineral rich mountains : Bourg d’Oisans, in Isere. Like me, he had been in love with crystals since childhood.

I appreciated Laurent for many other reasons. We shared the same approach on many subjects, ranging from our philosophy of living life “on the margin” to the ways of educating our children.

Moreover, to be on a team with him was simply a pleasure. He was always in control of his feelings, whether it be the delight of a treasure discovered, or fear in the face of an imminent danger.

Together, we felt ourselves always safe. Was this an exaggeration ? Perhaps.

It was relatively simple to get to the big find. It was close, it was easy to get to. Just what we wished for.

A huge cache lay within a profoundly deep and wide fissure of rough granite, about the size of the trunk of our old l950’s family Chevrolet. Some 800 kilos of crystals were neatly formed together, resembling a giant layered pastry.

There was enough work for a week if we could manage two shuttles per day.

We had already made four trips, when in the course of our work, we came up against ice, which had frozen many of the pieces together. We tried to heat up the cavity with gas camping stoves. It was taking a long time. Yet, it seemed like the best thing to do was to wait, and let things thaw out gradually so as not to damage any of the crystals.

We left our tools at the find, to specify clearly that we had claim on the deposit, this in accordance with the code of honor that exists between gem-hunters of the massif of Mont-Blanc.

Back at the refuge, everyone knew we had claimed our deposits at this precise place. Our friends could actually locate it with binoculars from the lodge, and keep guard over our site.

After leaving staff at the refuge with information on our destination, we went prospecting on the Courtes, on the other side of the glacier’s north face while we waited for the ice at our treasure find to thaw.

Returning to the refuge three days later to spend a night there, we prepared once again in the morning to return to our work. Objective: go up light, and then come down as heavy as possible.

In our backpacks we carried only what we would need to get the crystals out: journal, toilette paper, bubble wrap, old socks, that and nothing more. We could make the journey now with our eyes closed. No problems. Optimal weather forecasts.

But, upon finally arriving back, a horrible sight met our eyes–everything had been looted and destroyed ! The crystals, chiseled out, lay helter-skelter on a ledge. Hammering on ice which contains the crystals is the last thing a good gem-hunter wants to do, as the vibrations break up and destroy the surrounding crystals.

In less than four days of being away, our niche of marvels had become a spectacle of complete transformation, like a busy kitchen that suffered a cleaning storm. No broken plates here, however, but quartz crystals, morions and ankerite formed in circles around the quartz–rare objects–all pulverized.

In a rush, the thief had destroyed the major part of these treasures to gain perhaps just a few of them.

It was revolting–the chamber had been scraped down to its deepest corners.

There was only one thing left to do, we had to find this bastard.

In two rappels down from our work-site, we were on the glacier to examine the thief’s tracks. One was from the day before, another from the day before that. We could see that he came alone.

His footprints did not go toward the way-station. We surmised he was bivouacking near a moraine at the foot of the lower needle of the Amethystes. We hoped we could track him down and catch him.

No sooner do we set off over the glacier in pursuit, than Laurent stops me. “Cord!” he shouts. The “safe” word. It is clearly understood, when we say this word, there is no discussion. We are tied together !!

Safety procedures for walking on glaciers are clear : instead of traveling one in the footsteps of the other, or side by side, we are always connected by the safety cord, and we maintain a distance of twelve meters apart. At this point our safety line was taut.

I wanted to secure physica position, ready to stomp (like I would on a roach) on my teammate’s line, if he were to start sliding by me and down and into the crevasse. I saw him stop suddenly, hesitating, probing the snow with his ice ax. Then took a good amount of slack on the rope to jump at a spot that did not even seem to be open. At the precise moment when he took his jump, I saw him disappear, swallowed into the snow.

Without crampons on my boots, nor any place to seat myself in the soft sloping snow, my grip was too weak. I slid on my stomach, unable anchor myself onto anything solid. I was being dragged straight to the spot where Laurent had disappeared. I was hoping his fall into the hole would be a short one, so that the rope would stop pulling me in. But he was still very much in the fall as my head tilted to see down into a black chasm….

As I hurdled toward the bottom I remember how it felt–like having been beaten up, or like having been taken for a brief ride in the drum of a washing machine in spin mode. After my fall, I opened my eyes again, and I was positioned upright in the bluish half-light of a crevasse bottom, glued to Laurent. Our feet rested on a couch of snow. The space between these two ice walls was about fifty centimeters wide, which barely left room for us to turn around. Then the vice gradually tightened even more, as we slid on down another four meters deep. Laurent had nothing broken, and neither had I. He had good reflexes to push himself into position before I “joined” him. How lucky we were to fall and still be on our feet!

The cord saved us, he told me.

I didn’t understand.

He explained that he had passed through a bridge of snow, invisible to us at the top. Laurent was carrying a large bundle with him, which acted to brake the fall, in combination with the safety line. Even though I could not help sliding into the hole, it was because of my serving as a counterweight, as resistance, that Laurent’s fall was slowed down. All the snow that had collapsed along with him had more or less passed him by, to form a pile just perfect for us to land in.

Like corks on water, we landed to float on this snow, sinking down into it to our waists. Without the space between us and a good safety line and me serving up on top as ballast, Laurent would have gone straight down to smash his bones on hard ice, like ramming into concrete, before then being buried in all that snow, the very same snow into which we both landed safely. My fate would probably have been the same, if up on the glacier’s surface, we had proceeded without respecting the most basic safety rules.

Were we once again gifted a miracle from the Alps ? Yes, kind of. In all our exploring together, we did had some close calls.

“Not really any miracles now,” Laurent corrected me, “we’ll never get out of here. We have absolutely nothing to help us get back. All our gear is at the refuge.”

True. We had left everything there, beginning with our crampons and our head lamps.

In the fall, we had lost some of our gloves and, most importantly, our ice axes.

It very quickly entered our consciousness. the really nightmarish dimensions of this crevasse! Apart from being sandwiched between two walls of ice, we were quickly seized by the silence of the depths. There was only a single noise, the plop of the drops of water, which hammered the surface of our helmets.

Twenty meters above us the snow bridge remained intact, spanning the entire crevasse, as it pissed on us below. Our old, rotten gem-hunter jackets were already wet and we didn’t have any of the high-tech jacket/pants, Goretex combos, that usually line the bottom of our bag to be put on if something goes wrong. We left these, too, back at our lodge.

Plunged now into a sinister darkness, we had quickly become resentful of the cold radiating from these hostile ice walls.

“We have tons of snow balanced above us. When that bridge collapses all the way, that is the end, we will be crushed.”

Laurent was a pessimist. Not so, myself. I scratched the ice wall with the only sharp object I had, my car keys, in hopes of carving a first step for climbing up. The ice was very hard, but I didn’t have any other choices. I imagined myself scratching day and night in order to scrape steps into the ice, so that we were sure to arrive back. Not Laurent, who was completely worn out. He just sat down on his backpack.

Continuing on with my task, I reminded him about the Englishman, Joe Simpson, who was found at the bottom of an abyss. Left for dead by his friends, who were forced to cut their team’s life line cord for the sake of their own survival, Joe managed to get out of a monstrous crevasse, with only a broken leg. Gravely injured and alone, he pushed himself up from the depths and across a glacier at the base of the Andes, and did so by force of will in order to save himself.

Laurent didn’t listen to any of my words. He murmured, “Stop, Christophe…I know the story. I read the book two times. It was me who gave it to you…That’s it, now, it is finished, there is nothing more we can do.”

Never had I seen Laurent so somber, in such a dark mood, so detached.

Then, he said the name of his ex-teammate and he swore to me :

“He is the one who destroyed our cache !”

Laurent seemed devastated by this realization, and I could not believe it. How could it be possible ? How could one of our own betray us like this?

But Laurent continued explaining. Before taking the fall, Laurent had figured out that the tracks left in the snow were those of his old partner. The way this fellow walked like a duck, and the footprints Laurent saw were a veritable identity card in the snow. Also, these were popular Italian mountaineering shoes, Asolo brand, the same ones he wore when we saw him at the base camp.

Everything that Laurent told me, there at the bottom of that crevasse, was deeply upsetting. I, too, slumped back on my gear.

We began to feel the profound cold. Our own shivering grew audible.

Laurent seemed farther and farther away. I was afraid he would give up the game. To survive, it is necessary to always keep moving–rub your arms together and massage your thighs.

In the darkness of the crevasse, a gray-blue reflection already veiled my view of my friend Laurent. This made him look like a cadaver. It was not long before he yawned, and he closed his eyes.

I needed to do something ! I remembered another book, in which Louis Lachenal was trapped in a crevasse on Anapurna.

Right away I shook Laurent and tried to keep a conversation going, but this time I was more careful in my recounting of the events. Since the book was a great classic of Himalayan literature, he had certainly read it at least three times.

Lachenal and Herzog, after having conquered the first 8000 in 1950, were faced with an implacable cold, and had struggled all night against sleep, knowing that if they fell asleep, it would be the end.

Soon we were exchanging blows, and that helped us to get back on our feet. After these improvised boxing rounds, we went on to kick at the snow. Soon we were on all fours like two hapless dogs digging for bones. We feverishly mined down into the snow under our feet.

To replace our lost gloves, we covered our hands with the old socks we brought along for wrapping up the crystals. We started digging more, without knowing why, to a depth of two meters into the snow. This warmed us up considerably, and and to our delight, we found our ice axes!

By rummaging through all the pockets of our bags, and taking everything attached to our harnesses, we gathered together ten carabiners, an ice screw, and various pieces of line.

These items, each one on their own, might not seem that important, but it became clear that with all these bits and pieces, it was going to be possible to move on before we ended up like ice-cubes inside this big freezer.

Laurent knew of a technique he had learned during his training at ENSA to hang hooks in order to get out of a crevasse.

There was a way to use our one pin to screw into the ice, twice and at two diagonals, so that the areas you hollow out join inside the wall of ice. This formed a 10 millimeter in diameter mini-tunnel in which we could slide a cord, loop it, and hang a carabiner, through which to pass a safety line, connected to the harness of the one who would be climbing up and out first.

Laurent, in a vital burst, took the initiative to start carving steps with the ice ax.

Now he was really a great climber. Soon he was making his way out of the deepest part of the crevasse.

Laurent did not go directly toward the well of light, because at this point the crevasse grew too wide to keep going straight up without wearing crampons. He planned out a much less direct route, sometimes in zigzags, always taking into account the irregular spacing between the two walls of ice. To form each upward step, he would alternate from one wall of ice to the other. And so, he could always cut and secure the way up safely, easily, keeping his options open. Every two meters, he fixed an anchor point, an abalakof, with the ice screw. And so, we could secure ourselves on the climb up with the safety line.

Watching all this, I realized just how lucky I was to be with this particular high-mountain guide. He achieved a magnificent feat, all in one try, and with no faltering.

It took perhaps two hours or more, without time to rest, to make it up the twenty meters that separated us from the surface, reaching the ceiling formed by the snow bridge, and then piercing it, to discover the bright light of day.

We were on our way back, exhausted by our trials but profoundly grateful. He helped me make it back by supporting me along the way, because the physical immobility and waiting in the freezing cold at the bottom of the hole had weakened me considerably. I was experiencing border-line hypothermia. But all that paled in comparison to how lucky we felt to be in this beautiful moment, finally reaching our destination…

There was a well-hidden corner of the kitchen at the refuge lodge, with a table for six, that on a special occasion would fit close to a dozen of us. This was the hang-out spot for Olivier and the employees of the refuge, where guides and gem-hunters were regularly invited.

By this time, I spent all my summers at the base camp. Olivier was a very close friend who refused to let me pay for anything when I stayed with him. He even served me breakfast in bed, from time to time, after a particularly grueling adventure. I was, of course, not the only one to benefit from such preferential treatment. And, almost every evening, this was the “colleagues’ corner” where we would assemble to empty bottles of Genepi together.

This evening, the two of us must have been quite a sight, covered up and warming our feet in basins of hot water. Laurent was able to recover quickly. I, on the other hand, could not get rid of a convulsive tremor which completely consumed me head to toe, and lasted into the middle of the night.

But, a much more serious kind of trouble loomed right there in our midst, and soon after these unfortunate events, the wonderful ambiance of the base-camp on the Argentiere was to be no more.

Cowering among those at the table was the culprit who caused us our misfortune, trying to hide among the others looking like some worn-out dog. There were those who knew what he did, but who would never say anything–those who must have helped him, because all the crystals, including the stolen ones, were there at the refuge. And it pained us to realize that there were probably others sitting there who may have enabled our thief.

So this adventure ended, but it was also to be the end of a beautiful era. As we left the table we realized that the trust and friendship we shared here at the refuge was foutu, “gone forever.”

Laurent, following this complete betrayal, decided to finish out the season working with me, but also to abandon permanently his career as a gem-hunter.

Soon after this, Olivier left the refuge, and the crew there quit as well.

Laurent’s former partner had a hard time selling crystals that were “stolen goods.” He returned two or three more times to the massif of Mont-Blanc, and then he disappeared permanently from our circle.