Cursed Mine

(by Christophe Peray, Translation Eric White and Charlie Okiss )

August 1999, Sébastien Khayati finished his internship inside a wellbore to obtain his diploma of Soil Mechanics Engineer. Exhausted, oil stinking clothes, he joined his friend Potsky who was devouring a kebab in front of the television. The chanel was broadcasting a report about crystal prospectors in Mont Blanc Massif. It was love at first sight. Seb remained speechless in front of the red fluorines from Pointe Kurtz, the sublime high-mountain landscapes and the work of a team doing rope aerobatics.

– “That’s it ! That’s what I want to do with my life !” he said to his friend.

But before we follow Sebastien on his wanderings, let me tell you about a particular place hidden in the heart of the Mont Blanc massif. The wall was crossed by thin galleries leading to collapsed cavities. For the most part, crystals were broken but their quantity seemed inexhaustible. I gave a name to this sector: The Mine.

The rock around the mine bordered the glacier and when it completely withdrew with the beginning of warming in the 1990’s, the fragile edifice that had always been contained by the thickness of the ice, began to collapse in successive parts.

The Mine started to stabilize 2004. I was finally able to settle there. The access was easy because the landslides had ended up making it lose much of his inclination. It now resembled a maze of large blocks sagging into deep bowels.

I don’t know if all the mazes hosts a minotaur, but the monster looked like the rock itself, permanently auto-devouring. I could hear his stomach under my feet, bringing to the surface his flatuousness and deep cracks.

The techniques of extracting the rock that I allowed myself in the Mine were very rudimentary:

A mine without drilling machine ? Or explosive? It’s absurd!

Indeed, any mechanical tool is prohibited in the Mont Blanc massif. They participate, under the law, in the degradation of a protected site.

Prospectors benefit at most, not from a right, but from a tolerance to tow the rocks with the force of the arms, or move them with ropes and climbing gear. Hammers and chisels are authorized by a circular note from the Ministry of Environment, but that’s all. This tooling does not represent a large strike force. A similarity with the Neolithic period. An archaic rule of the game but finally quite pleasant to put in practice. The activity of crystal prospector has become an exercise of patience and discretion. We obviously all have our little tricks to help in our task. Personally, after spotting the weakness points on the walls, I take advantage of the ice, this natural explosive, which expands every winter, and widens the cracks of the rock until it bursts. By dint of observations, I end up sneaking in without making noise or disturbing anything.

Seb had begun to release exceptional siderite crystals in abandoned mine galleries around Grenoble, but his dream was to prospect the partly unexplored Mont Blanc massif.

So he pitched his tent in front of the glaciers. The effect he felt there was powerful. He became aware of the dizzying dimensions of these mountains where every step is a matter of survival.

His firsts incursions on glaciers were done around the “rognons” (literally “kidneys” in french). These are areas that have recently been dried up, after being flattened and thind by the ice. The fault of rising temperatures.

Remembering his first steps in the massif, he says: “I was bringing back from these kidneys only ugly pieces.”

At the hut, he recognized the crystal hunters in their dirty clothes. Most of them had 20 or 30 years of experience. The less grumpy of them would give a few answers to his questions, but wouldn’t take him on a trip, especially to explore a spot with countless rockfalls. Too dangerous !

On my side, same scenario. I was working at the mine without any co-worker, and I had the same struggle finding a partner to share the adventure with.

In the meantime, I was using trickery to remain unseen, constantly changing itineraries, and preferring night returns.

The more I was working at the Mine, the more crystals were showing up. Inexhaustible ! I was bringing back heavier and heavier backpacks down the valley, more and more often. No time for rest, I was afraid to see my secret revealed.

It was in this context of loneliness that the curse seemed to reach me.

It was not related to occult powers, but about this excessive relationship with the stone, through which my body and reason diminished.

On July 28, 2005, my friend Laurent Chatel proposed me to suspend this slave labor, and escape with him to a beautiful and wild prospecting area, as we did daily ten years earlier. Geologist and crystal prospector, business leader, cliff security expert, mountain guide, and so on, Laurent was considered the guardian angel of risky areas. But that day, on the crest of the Rochassiers, a platform dropped under his feet. The surprise and horror were total. In a split second, I was losing one of my dearest friends. I couldn’t believe it. The day after his funerals, I went back to the Mine to put my things away. The next moment, as I went down on the glacier with my head loose, I fell at the bottom of a crevasse. suddendly I felt a very sharp pain in my back. A pain that never left.

Tragedies have this power to bind us deeply not only to the beings we lose, but also at the places where they occured.

But there was no question about stopping my activity. Total opposite! The need to continue climbing, and to prospect, became even stronger, out of fidelity for the memory of my friend who had been rooted forever.

But let’s go back to Sebastien Khayati. We could say Seb has always had a knak for finding crystals. He is of these prospectors who could round off any angle of a cavity with his body. By reptation, he is able to interfere into the most sinuous interstices. When is arms no longer have room to move, he manages to grasp with his teeth the bothering rocks in front of his face to roll them with his chin, and swipe them under his body, dragging them by rippling backwards. This way, he explores the depths of the mountains, while ” reassuring ” me:

– “If you can get into the bottom of a hole, you can always get out of it.”

“Yes! so far! “

After Laurent’s accident, I had made the decision to travel the mountains only solo, and to abandon this too scabrous mine. However, after I met Sébastien and especially after that moment, he told me about his experiences in dozens of secret mines across France, it became impossible not to present him the Minotaur.

Back in the den of the beast, new omens caught our eyes, but I no longer felt the same enthusiasm to play the big blocks mover, as this pain in the back was sharp, and continued to spread to other areas of my body.

I was nearly breaking away with the mine, instead of Seb who was celebrating every find, including a promising piece, by releasing his emotions with exclamations and shouts of joy. It’s in his deepest nature, I have never seen this feeling decreased in Sebastien. A way for him to ward off the evil spirits ?

He also had his lot of sufferings and tumbles.

Certainly ! The proof are the disproportionate amount of rocks he was collecting in his backpack, and the consequences on his health.

By over-loading the mule, as he still does, he knows perfectly well what awaits him: the headstone, at best the wheelchair.

Seb obeys the laws of all mines in which the self-destruction of the body is programmed faster than in normal life.

Very recently, just over a year ago, I came back near the Mine. In the meantime, we had made other trips together, in alpine mode, in the massif des Droites or Les Courtes. But that day, he told me on the phone that he was on a big thing, with fantastic gwindels as a fair reward.

These last ones he exhibited at the last mineral show of Sainte-Marie-aux-Mines, in Alsace.

I couldn’t miss the event. As I approached the Mine to join him from afar, I could already hear him swearing, talking to the spirits, and exulting with as much enthusiasm as an Italian supporter in a football stadium.

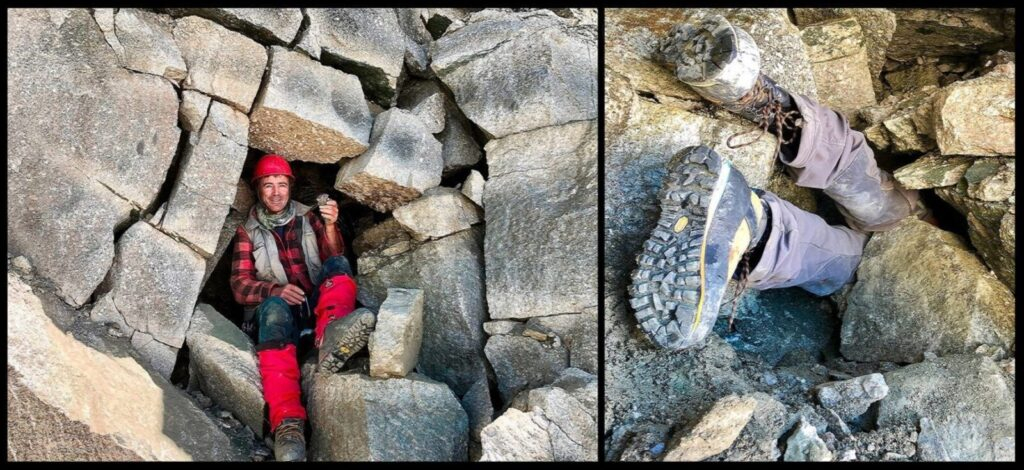

I found him upside down at the bottom of a crack. The only thing I could see was his shoes agitating under stacks off large blocs, comparable to an Inca temple after an earthquake. To worsen the situation, rocks were falling down from the crests, whistling like falling bombs, or close to the edges like cannonballs. From time to time, they would hit our position in ruins, on the verge to collapse.

My disability did not allow me to do much to help him. So I was asking myself the endless question “what the heck are we doing here?”.

The prospectors say, to justify their activity, that if the crystals are not picked up in time, they are inevitably crushed and transformed into moraine sand.

Totally true! And especially at the Mine where the rock is under the grip of a slow tectonic bubbling. But this mission of savior is not the flame that motivates our activity. If, at that time, Seb puts his life at risk, it is because he must be subject to a much deeper necessity than that any moral justification.

Could it be the prospect of a financial reward that motivates him in this quest for the crystal throughout the year?

Nope! Because Seb, the well-educated, could have worked in a CEA* lab or benefited from a very comfortable salary in a company like Total…

As a result, the pecuniary explanation does not fit. The real reason is necessarily elsewhere.

So I asked him:

– “Why did you come here, to put yourself in this situation ?”

Is it the love for the crystal? A rejection of living in contact with humans? How can a astrophysics enthusiast like you, who has the vocation to keep his head in the stars, like to roll in the gravels with the constant anguish to die here?”

In response, Seb emerged from his hole with his hands and head covered in blood. He was holding an ultra luminous bypiramidal quartz. I saw in his ecstatic eyes the same radiance as in the crystal. I could hear all his overwhelmed sensibility expessed, once again, by a groan coming from so far, too deep to be just coming from the simple feeling of a new discovery.

I believe that, at this very precise moment, Seb belonged body and soul to the mine, and his language was no longer based on words and phrases, which are normally so dear to him, but by a mode of communication that exclusively uses “pwouaaaaaaaaaas” or “wouaaaaaaaaas”

Then I tried to interrupt him:

– “Seb? Where are you? “

But Seb wasn’t answering.

Seb was far away. Perhaps he had returned to a time where stones, animals, humans spoke the same language…

Then he came back.

He offered me his bipyramidal quartz, while he was still holding it to make it shine under the sun.

– “I’ll call him Minos! I said.

“That’s a nice name,” he replied.

It suits well the piece. And it reminds me the King Minos of Crete, the Labyrinth and his Minotaur.”

Anyways! All these wanderings do not tel us what we are really looking for, beyond these rocks, in this chaos as if the need to be there exceeded us. Because crystals are useless. Simple objects of daydreaming, we collect them like they represent a vital need. They impel us to break all the alpinism rules that normally forces us to be cautious, and to betray the prudent promises we endlessly repeat to our loved ones. All this, to satisfy this need, away from prying eyes, but not from the Minautor and the curse that wears our bodies.

I am convinced that this instinct is intimately linked to a distant ancestor who was looking for a piece of flint. We have to go back long before the Neolithic, to the australopithecus, three million years ago, who began to collect stones to carve and invent the first tools and weapons. We can infer that this taste for crystals also brings us back to one of the oldest activities in the world.

Today, we call this need to find THE rock, an “atavism”! The word sounds like the name of a disease, but it is not. It means a character trait inside our genes that reappears after more or less long absences, in the great evolution of life.

If the quartz we discover is no longer used to make arrowheads, they nevertheless retain, in the deepest strata of our being, all the value of objects both indispensable and beautiful, without knowing exactly why.

But back to that day with Sébastien at the Mine. While I accompanied him into his underground explorations, I did not recognize the place, as it had been turned upside down by the falling stones and the subsidence. There was now a rope connected to spits to secure the walk. We could have shared with other teams as there were tools left behind with a name on a card. Today, half a dozen prospectors share the drunkenness of the mine. There are pockets* for each of them and they find mostly quartz crystals, always very clear, sometimes very large. Gwindels also nest there, and a very large number of so-called “faden” quartz, recognizable with their white filaments that pass through their water clear center, in a whirlwind of delicate clouds.

A month later, early autumn 2018, the large plate above the place where Seb worked broke down and it ran down the entire wall. Pulverized, the remains slided underneath the glacier where they disappeared swallowed by the mouths of deep crevices.

This plate, which we had nicknamed “the wall of the Inca temple,” took with it much of its treasure. But others appeared behind. It’s reassuring! Behind each landslide are other bright stones. In the Alps, crystals will always emerge, as long as the mountains exist. Their light will always give an extreme feeling of happiness, or misfortune, for those who take all the risks to reveal it.

CEA: Atomic Energy Commissioner.

Pocket: a cavity filled with crystals inside the rock or on its surface.

Photo 1 : The Bipyramided Minos Crystal.

Photo 2 : Sebastien, bloodied, contemplating a gwindel.

Photo 3 : I am sitting at the entrance of the Mine with the Minos crystal in my hand.

Photo 4 : Seb’s feet after he plunged into a crack in the Mine to grab a crystal.